Debunking the Gender Pay Gap: Fact, Fiction, or Fairy Tale?

Do Women Earn Less than Men?

How many times have you read an article online that says women make less money than men, that there’s a wage gap between men and women? Of course, these claims are all backed by numbers and data sets: percentages, salary ranges, and cents on the dollar. But how do you distinguish between a source that presents the facts in their full context and one that may be incomplete or potentially misleading without greater scrutiny?

Is Gender Income Inequality Real?

The gender pay gap is a complex issue, and there are many factors that you have to take into account before you can truly discern whether the math is mathing. For instance, does the study you’re reviewing look at part-time workers, or is it limited to full-time employees only?

Some studies focus exclusively on women who work at least 40 hours a week, year-round. This kind of study would exclude a large number of gig workers, people who work seasonal jobs, part-time workers, and workers who had to leave the workforce for any period of time during the year, whether due to an illness, because of an unforeseen emergency, or to care for kids or elderly parents.

All that to say, it’s important to understand what the study is actually telling you and about what group of workers.

It’s Complicated: Let’s Unpack!

It’s easy to feel unsure when even the data seems to disagree. Let’s look at the facts first. According to the Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan fact tank, the gender pay gap in the U.S. has narrowed slightly over the last two decades. That’s good news, right?

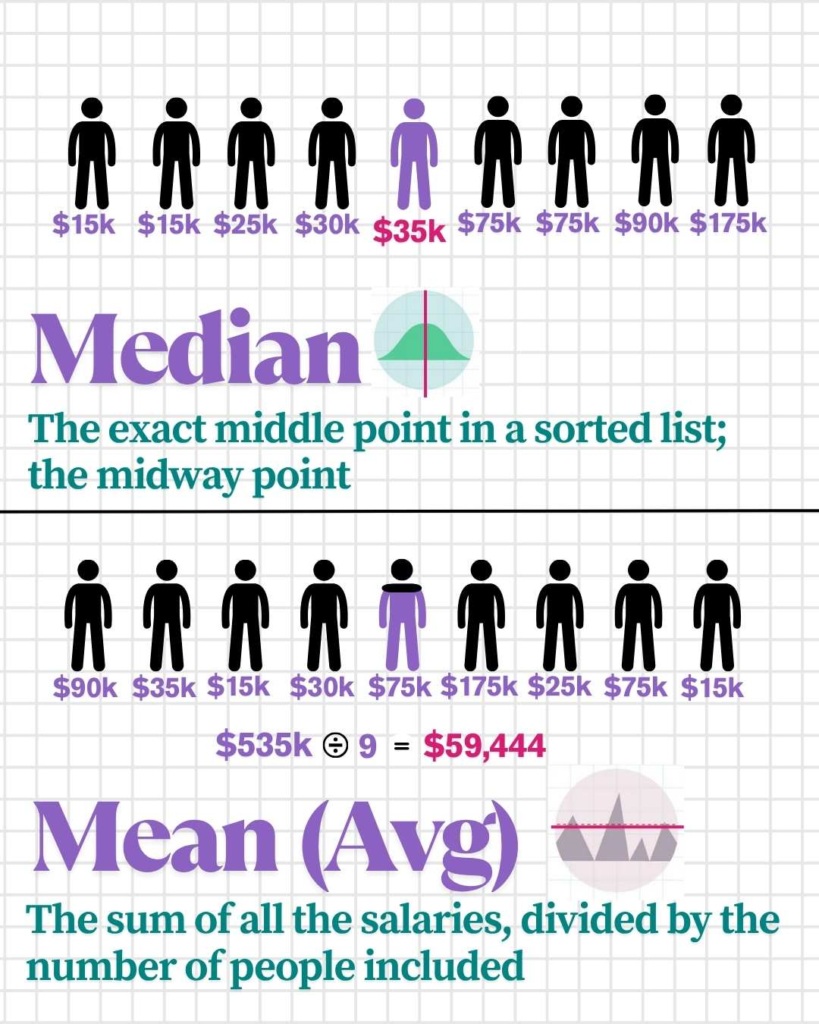

Sort of. It’s an accurate statement, to be sure, but the fact remains that women’s median pay (the wage amount exactly at the middle of all wages for a particular career) has increased by only a few cents on the dollar over the past 20 years. In 2002, women earned about 80 cents for every dollar earned by men.

In 2022, women earned about 82 cents for every dollar earned by men, according to Pew Research Center. That number reflects median pay across full- and part-time workers. That means that the median pay for women has gone up by only pennies when compared to the median pay of men. Sure, the gender wage gap has narrowed, but not by much. And it’s clear that it still exists.

Median vs. Mean (Average) Pay

When looking at data about salaries, it makes more sense to look at the median pay, which represents the midway point of all wages for that career. Why? Because it signals that about half the people in that field are making less than the median pay and half are making more. When looking at the median pay, you’ll still have extremes on both ends, but those extremes won’t skew the data, like they might if you’re looking at the mean, or average, pay.

Let’s say you’re thinking about going into marketing, so you take a look at entry-level salaries for marketing associates. First, you need to take into account factors like location, industry, and size of the company hiring. Bigger companies tend to pay more, just like a tech company may pay a marketing associate more than a health care facility would, and likewise, a company based in a big city is going to offer higher pay than one based in a small town. These are all factors you have to consider when looking at the data to discern for yourself whether gender plays a role in income inequality or it’s just a wage gap gender myth.

There is a lot of misleading data about the gender pay gap from a variety of sources that might seem authoritative at first, or even second, glance. But once you know what to look for, you’ll be able to break it down and discern for yourself.

In 2025, Is the Gender Pay Gap a Myth?

In 1982, women made about 65 cents to the dollar that men made, and that gap decreased to about 82 cents to the dollar in 2022, but let’s talk 2025.

According to Payscale’s 2025 Gender Pay Gap Report (GPGR), despite pay transparency laws in many states, the closing of the gender pay gap has stalled nationwide, with systemic barriers still limiting women’s earnings.

Payscale’s analysis shows that in 2025, women still make only 83 cents for every dollar men make. While this remains unchanged from last year, according to AAUW, Equal Pay Day regressed more than two weeks this year, which means that women must work that much longer to make the same earnings as men in 2025, when compared to 2024.

Gender Pay Gap Debunked:

Fact, Fiction, or Fairy Tale

What questions should you ask when you see a stat like this? Let’s go through the most popular claims about why the gender pay gap exists, because there is a lot to unpack, and the answers can be complicated.

Addressing Common Misconceptions

There’s a common stereotype that says women are hesitant to negotiate because they don’t want to “rock the boat,” but the latest research indicates that this isn’t necessarily true. In fact, recent studies have found that women, particularly those with graduate degrees like MBAs, are actually more likely to negotiate their salaries than men.

You’re right to question this – here’s what the research actually shows.

According to a new study by Laura Kray, a leading researcher at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business, the widespread assumption that women don’t ask for higher pay is not just outdated, it’s false. In a 2023 interview, Kray said:

While men in the past may have been more likely than women to negotiate, the gender difference has since reversed. Continuing to put the blame on women for not negotiating away the gender pay gap does double damage, perpetuating gender stereotypes and weakening efforts to fight them.

So, contrary to popular belief, Kray found that professional women now negotiate their salaries more often than men do, but they get turned down more often than men do as well.

Income Inequality by Gender

The researchers on Kray’s team surveyed a nationally representative sample, confirming that there is a popular perception that men negotiate more than women and are more likely to get higher pay without having to ask for it.

But when Kray and her co-authors analyzed a survey of graduates from a top MBA program between 2015 to 2019, the findings did not match that popular perception. In fact, the researchers found that 54% of the women graduates reported negotiating their job offers, compared to just 44% of the male graduates.

Likewise, in a 2024 study by Vanderbilt Business School professor Jessica A. Kennedy, whose areas of expertise include negotiation, business ethics, and gender in the workplace, found that the tendency for men to negotiate more than women has become obsolete, and the prevailing narrative that women don’t negotiate or ask for higher pay is now a myth.

The same Vanderbilt study noted that the gender pay gap has increased for the first time in two decades, with full-time, year-round working women’s median earnings at 82.7% compared to those of their male counterparts, according to U.S. census data. In 2022, women earned 84% of what men did, so this represents a serious backslide, especially given that the 2004 wage gap for men and women was 81%–or 81 cents for women to the dollar that men earned.

Kennedy acknowledges that studying income inequality by gender can be tricky in a politically polarized environment. Focusing on income inequality in the U.S. can get messy, but when it’s your salary and 401(k) on the line, there is no overthinking this. Kennedy said:

Sometimes I have concerns that comparing men and women fuels an unproductive gender war instead of illuminating the real issue, but the point is that employers should be paying in justifiable, transparent ways with equal pay for equal responsibilities. A pay gap by itself doesn’t necessarily indicate unfairness, but too often, it causes people to invent false narratives about people who command fewer resources, and that’s a real problem. We can’t deal with a problem we don’t see accurately.

Gender Pay by Occupation

Although the gender wage gap in the U.S. has moved by a few pennies to the dollar over the last two decades, if you break it down by income level, the gap for women earning middle and lower wages may have shrunk a bit, but the gap for women with higher salaries—even though they often have more room to negotiate—has actually increased.

Kray’s research team found that not only does the wage gap increase for women with higher pay but it continues to grow as they get older and go up the corporate ladder. In fact, the study shows that women earn 88% of what men make after finishing an MBA, but only 63% of what men make 10 years later. That is a significant and very concerning difference.

According to Kray’s findings, this income inequality by gender among MBA graduates “is especially notable considering the nearly identical skills and qualifications held by men and women at the time the degree is conferred.”

Wage Gap for Men and Women Over a Lifetime

The good news is that younger women–those of us in our late 20s and early 30s–have gotten closer to bridging the gender pay gap over the last few years. The bad news? Pew found that the earnings for women aged 25-34 have not budged from about 90 cents to the dollar compared to men of the same age.

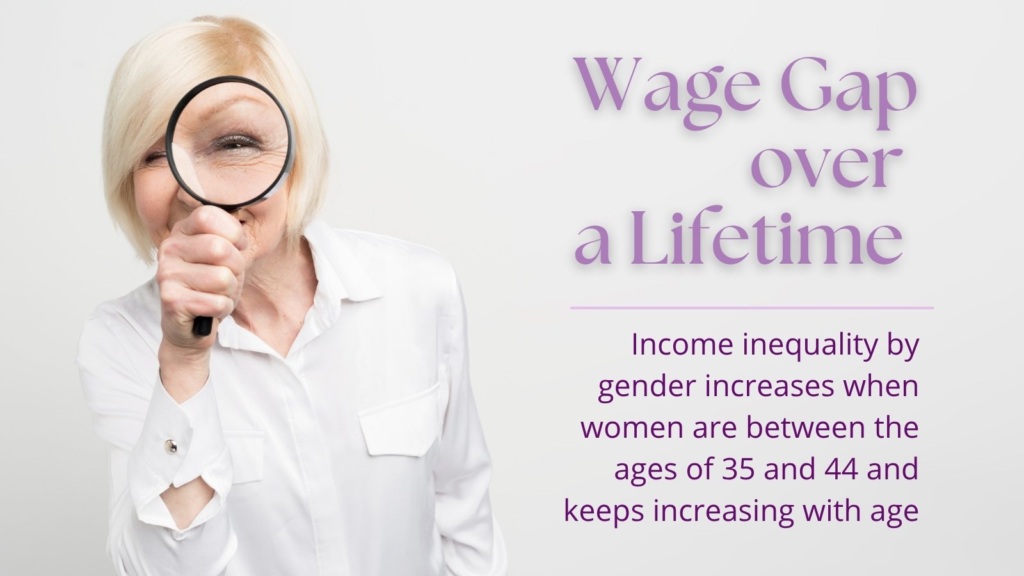

And even as closing the gap of income inequality by gender might now appear within reach for women at the start of their careers, the wage gap tends to widen as they age.

Let’s take a look, like Pew did, at women who were 25 to 34 in 2010, when women earned 92% as much as men their age, compared with 83% for women overall–that is, when you take into account women of all ages for that year. By 2022, this group of women, who were now 37 to 46, earned just 84% as much as men of the same age.

How Does Gender Inequality Affect Gen Z Women?

According to a recent study, young women starting their careers in entry-level roles make 93% as much as their male counterparts. ZipRecruiter surveyed around 3,000 people in the U.S., and post-graduate women reported making $67,500 annually, while men made $72,700.

Study after study has shown that the gender wage gap widens for women as they get older. This is a disturbing pattern that has repeated itself among women in the same age range in previous years, and it may well be the future for women entering the workforce now, according to Pew.Cutting Through the Noise: Evidence-Based Findings on the Gender Pay Gap

Income inequality by gender increases when women are between the ages of 35 and 44. For example, in 2022 women aged 25 to 34 earned about 92% as much as their male counterparts, but women who were 35 to 54 earned only 83% as much, and women who were 55 to 64 earned just 79% as much. Sadly, this pattern has not changed in over four decades, as Pew found.

So while the gender pay gap in the U.S. has narrowed very slightly over the past two decades, financial analysts found evidence that shows it will take 134 years to reach parity, according to recent data from JPMorgan:

If current trends persist, it is projected that global gender equality will not be realized until the 22nd century. This means that a girl born today would have to wait until her 97th birthday, which is beyond the expected lifespan in every country, to experience a truly equal society.

The JP Morgan study found that the U.S. gender pay gap increased to about 17% in 2024 and remained unchanged in Europe, at almost 13%.